B. Ethical Dilemma

An Ethical Dilemma: A Typical Case

Just to get things rolling and to introduce ethics, let’s begin with a situation, a quick look at a case that might be described as “typical” in bioethics or in public health ethics.

Ethical Dilemma: Ebola

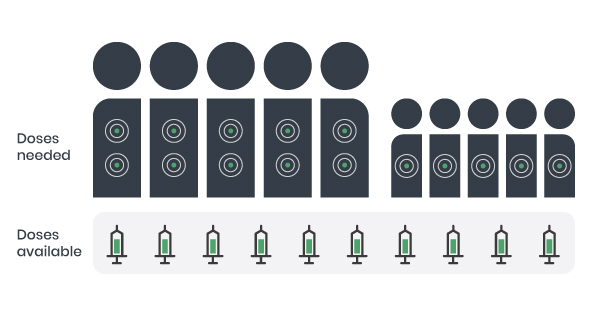

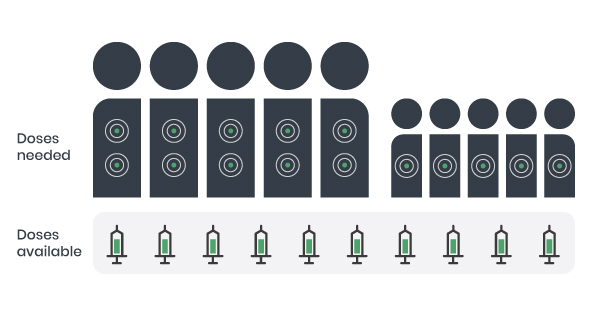

Imagine that you work in a clinic and 10 patients that are infected with Ebola are all admitted at once. There are five adults and five children. Among the adults are 2 volunteer care workers. You have only 10 doses of an antiviral medication, but the treatment requires 2 doses for adults and 1 dose for children to be effective. Because you do not have enough doses to treat everyone, you must decide how to distribute them.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Ethics Can Help to Give Us a Common Language for Exploring Issues and Making Decisions

In this and in other situations, we can say that behind all of the choices or actions that one might have to consider, there are values, principles and ethical theories that are not universally agreed-upon. The goal here is not to debate whether the positions that we have attached to the different choices line up perfectly with the list of potential actions in this example, but rather to see how ethics can help to make those ethical values and theoretical positions more explicit. So maybe this exercise can show how ethics helps us to see the issues more clearly and give us a common language for thinking and deliberating about them before making decisions.

Reading

The following is an optional additional reading you may pursue for an introduction to ethical reasoning as it relates to public health.

Dawson, A. (2011). Resetting the Parameters: Public Health as the Foundation for Public Health Ethics. In A. Dawson (Ed.), Public Health Ethics: Key Concepts and Issues in Policy and Practice (pp. 1-19). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

This introductory chapter provides a fine overview of an approach to ethical reasoning within the context of the aims, concerns and issues relevant to public health.

Two Ways of Looking at Choices People Make

Another goal here is to highlight two main ways of looking at the choices that people make. We could ask people what they do, or what they would do, if they were placed in a given situation. Then we could look at the values, principles or theoretical positions that were guiding those choices. This would be to do descriptive ethics, because we would be describing the values that guide practice by studying, documenting and describing what people do in their moral lives. The other option is to adopt a normative role by not only considering what people do, but also what they ought to do. When we bring in the “ought”, or should, we are entering into the field of normative ethics, and the language becomes prescriptive.

Pause and Ponder

Returning to the Ebola Ethical Dilemma above, let’s imagine you are discussing this case with a colleague. How do things change if you discuss it in terms of descriptive ethics versus normative ethics? How do you discuss different choices? What if you disagree with someone’s choice?

In most of what you will find in public health ethics, the “ought” of normative ethics is usually present. That is, public health ethics is a critical and prescriptive discussion about what we ought to do or not do in public health (i.e., it considers a range of complex factors and decides what action should be taken).

Extreme Example, but also Realistic

We called the above example a typical case because a lot of ethics cases describe extreme situations. The fact that it is a bit extreme does not make it unrealistic – it is just not an everyday occurrence. Here is an excerpt from a recent article by Dr. Bruce Laurence, a Director of Public Health in Bath, England. In a discussion of how public health ethics applies in his real world, he says that...

One striking example of the problem of expecting easy solutions to difficult problems was during the 2009 Swine Flu pandemic when for a short while we thought that […] we might have to make really difficult decisions about use or withholding life saving resources on a mass scale.

He goes on to say that when it came to getting ethical guidance on what to do...

A paper was commissioned […] to look at the ethics of making such clinical decisions […] but to me at the front line of the pandemic, it made it no easier to know what to do.

This illustrates the challenge of using ethics tools to help us tackle specific and difficult problems. Guides, frameworks and resources are available to help us, but they won’t do the hard work for us. That is, they may help us to raise issues and perhaps help us to discuss them with colleagues, but ultimately they will not make the hard decisions for us about what to do. However, they help us to be better informed (even if that doesn’t make life easier) and better prepared when we do make a decision. They can also help to make our decisions more explicit and assist us in explaining them to others.

Why Public Health Ethics is Important

Is Public Health Ethics Important?

Here’s a really straightforward way of answering this question. Let’s revisit our Ebola Ethical Dilemma again.

Ethical Dilemma: Ebola

Imagine that you work in a clinic and 10 patients that are infected with Ebola are all admitted at once. There are five adults and five children. Among the adults are 2 volunteer care workers. You have only 10 doses of an antiviral medication, but the treatment requires 2 doses for adults and 1 dose for children to be effective. Because you do not have enough doses to treat everyone, you must decide how to distribute them.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

What should you do?

- Give one dose to everyone.

- Give one does to each child and 2 doses to 2 adults.

- Organize a lottery (random assignments to individuals).

- Give the doses to the most disadvantaged first.

- Treat the care workers first.

Does the outcome matter?

If yes, then public health ethics matters.

The choice that is made in a situation like this, or in any case involving the allocation of scarce resources, clearly has important effects upon the lives of the people involved. Some might die or some might have their quality of life dramatically diminished if we choose one course of action over another. Is the choice important? The answer is clearly ‘Yes’. The importance of the choice shows the importance of the ethics at play during decision making, as the choice is informed through ethical deliberation.

Public health ethics is important because it can help us to:

- See ethical issues

- Deliberate about options

- Make better decisions (not necessarily easier, but more ethically informed), and

- Morally justify them.

Public health ethics enables us to do this in a way that fits best specifically with public health practice.

One more way of underlining the importance of public health ethics is to point out that there have been calls for improving ethical competency (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2006) for practitioners and for more investment to support the development of ethics-related competencies (Health Canada, 2003) for many years. There has been growing awareness that professionalism includes various kinds of ethical literacy, as demonstrated in an article from the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (2007). The article outlines the importance of being knowledgeable about ethical values, concepts and decision-making and engaging in critical thinking about ethical issues in a clinical and professional practice.

The Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada document (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2006) notes that important “values in public health include a commitment to equity, social justice and sustainable development, recognition of the importance of the health of the community as well as the individual, and respect for diversity, self-determination, empowerment, and community participation” and that these values “form the context within which the competencies are practiced” (p. 3). The ensemble of competencies for the practice of public health take their shape from and unfold within an ethical backdrop. Ethical practice is the context for public health practice in Canada.

In addition to this, outside of Canada’s borders, ethics competencies are also recognized as important. For example, in the United States, specific competencies in ethics such as the ability to discuss the roles of ethics and evidence as dimensions of policy making are required elements for accreditation of schools of public health (Council on Education for Public Health, 2016, p. 17).